Library Reference Number: 214

Submarine Launched Aircraft - Surcouf

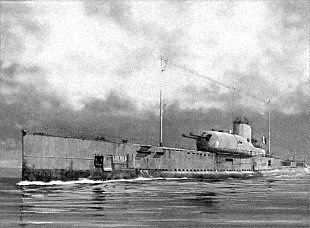

On reading a recent addition to the SSAA library about the Japanese 'Iwo Jima' class submarines carrying aircraft, I was reminded of an article I had written for a book some years before and where this aspect of naval aviation had been covered in some detail. In recent years, there have even been submarine launches of F16 fighter and stealth aircraft by the US Navy in a manner akin to a missile but the idea of transporting and launching aircraft from a submarine goes back to the years following World War One. The following article is a massively abridged and condensed article about the French submarine Surcouf; the first one ever to carry an aircraft inside a watertight hanger.

Upon conclusion of World War One, French military strategists turned their attention towards the island nation they now regarded as a potential competitor and future enemy. Britain, with her vast empire, represented a threat to French colonial aspirations and expansion. It seemed likely that these interests would clash at some future date and war between Britain and France would become inevitable.

Upon conclusion of World War One, French military strategists turned their attention towards the island nation they now regarded as a potential competitor and future enemy. Britain, with her vast empire, represented a threat to French colonial aspirations and expansion. It seemed likely that these interests would clash at some future date and war between Britain and France would become inevitable.

The recent war had amply demonstrated just how reliant Britain had been on its merchant fleet bringing munitions and supplies from the USA. German efforts designed to stop resupply using submarines had almost succeeded and nearly accomplished what the powerful German High Seas Fleet couldn't.

In 1922, French Admiral Drujon submitted a plan for seven long range submarines which would, during time of the anticipated conflict, would sail on ninety-day missions with orders to sink British ships. After much debate and consideration, order number 0926, for the first of these vessels, was placed with a shipyard in Cherbourg.

Construction began on 1st July 1927 and the revolutionary vessel was launched on 18th November 1929. The vessel was named Surcouf after the popular French naval hero, Robert Surcouf, whose bold exploits against the English in the Indian Ocean were legendary among his countrymen.

When launched, Surcouf was the largest submarine in the World. She was was 361 feet long and displaced 3304 tons when surfaced and 4318 tons when submerged. The two giant 3800-hp Sulze diesel engines could drive the surfaced vessel for 10,000 miles without refuelling at a speed of 10 knots. Maximum speed was 19 knots while surfaced and 8 knots while submerged. Her underwater duration was limited to just one hour and propulsion in this mode was provided by electric motors and batteries.

She was well equipped for the envisaged role with two massive 203mm (8”) guns mounted in a gun turret installed just forward of the conning tower. Two 37mm cannons, two Hotchkiss machine guns and six torpedo tubes fitted near the tail were also available for use when the vessel was surfaced. When submerged, the four internal torpedo tubes were deemed to be the principal method of attack.

Spotting a potential target over the horizon was always a major drawback of having such a low free board above the water when surfaced. At best, and due to the curvature of the Earth, the limits of vision was and is about seven miles. To overcome this, some submarines had conducted experiments using large tethered kites capable of lifting a man aloft and towing the assembly behind the vessel.

This method had the advantage that the kite could be recovered and folded into a small space but was limited to days when adequate wind was available and risky during an emergency since there would have been little time to recover the kite and the line would have been cut to leave the hapless pilot to his own devices.

At the Battle of Jutland, the British Navy had successfully launched a powered aircraft from a ramp built on the gun barrels of HMS Engadene but while the pilot and navigator of the plane could see what Admirals Jellicoe and Beatty couldn't; they were unable to report this due to a technical failure of their radio equipment. A similar radio failure at the Battle of Midway in 1942 blinded the Japanese about the true extent of US Naval forces pitted against them.

To meet this aerial spotting criteria, the Surcouf was built with a cylindrical watertight hanger located behind the conning tower and where a Besson MB411-AFN seaplane was stored in ‘kit form’ and from where it could be rolled out and launched from a ramp.

From a strategic viewpoint, the existence of such a potent weapon served as a powerful deterrent during peacetime while presenting an awesome threat during war. Outwardly, she appeared as an exemplar of technological progress and innovation denied to many others. Surcouf represented a symbol of French pride and authority, often undertaking tours to French territories in the Mediterranean Sea then later to French territories in the Caribbean.

In reality though, the Surcouf was unreliable and suffered from several crucial design defects. She was prone to leaks, particularly within the gun turret, and which seriously affected the trim of the craft when submerged. On more than one occasion, the Surcouf dived uncontrollably well below her specified maximum depth of 80 metres but where safe operation was resumed without loss.

Her diesel engines, electric motors and other systems often broke down and spare parts were almost impossible to obtain due to her unique design. In some cases, the problems were an inherent part of the design and could not be resolved..The additional weight and wind-shear above the deck caused the vessel to to roll badly even in a modest swell and where it was impossible to assemble and launch the aircraft in all but dead calm conditions. During stormy weather, acid was apt to spill from her batteries. Diving meant securing twenty-four vents and typically took about two and half minutes to complete during which time she was vulnerable to aerial attack. In an age of rapidly developing aircraft with greater capability and range, there were doubts whether Surcouf and other vessels of this design could ever operate safely in areas where land based aircraft could reach. Overall, Surcouf was far less than the planners had envisaged and future development of the design was cancelled. Surcouf would remain as a sole member of her class. It would fill a modest tome to recount details concerning this submarine aircraft carrier during its service in World War Two, but brevity is best for this web article dealing more with aviation.

It's just enough to say that Surcouf was undergoing repairs (again) at Brest when it became obvious that the French Government was close to surrender. In haste, the Surcouf sailed to England and where, upon arrival, few Allied Commanders recognised any strategic value afforded by its presence. General Charles de Gaulle, leader of the Free French Forces and living in exile in the UK, disagreed vehemently, and insisted that Surcouf was a symbol of French pride despite the fact that most of the original crew chose repatriation rather than serve under his command. The new crew, often taken from 'interrogation centres', were led by surviving members of the 'old crew'. Like other vessels rejoining the conflict under the Allied Banner, a small team of observers were placed aboard and reported back to the Admiralty without reference to crew, captain or officers. In most cases, this worked well and without fuss. Polish crews, in particular, worked alongside these English reporters without much friction but aboard Surcouf, their presence was continuously resented and grew worse as some of the exploits became more extreme and dangerous.

Sent to the Western Atlantic on convoy escort duties and far from the possibility of enemy aircraft, she was reported as having taken up wrong positions and representing a hazard to the convoys she was was supposed to protect. Even some merchant seamen wondered what side she was on and with reasonable doubt. On one occasion, she even attempted a botched attack on an American Task Force including the aircraft carrier USS Wasp and the heavy cruiser USS Quincy and at a time before the USA had even entered into the war! The consequences of this action might still send a shiver down the spine over what the consequences might have been!

Despite explicit orders to the contrary, the Free French Navy undertook an independent attack on the Isles of Miquelon and St Pierre and where it had been suspected that close proximity to Newfoundland and powerful radio transmitters were relaying convoy assembly information to the Germans. Although probably true, Winston Churchill was compelled to apologise to US President Theodore Roosevelt concerning this issue.

On the morning of December 7th, 1941, four Japanese aircraft carriers launched an assault on the US Naval Base at Pearl Harbour in Hawaii. Despite expectation of hostilities and military intelligence of intent supplied from Britain, the USA had done little to bolster defences or even accept the threat was real. As a consequence, the Japanese raid was highly successful but lacking in a singular and crucial detail. The US aircraft carriers had been at sea when the raid took place and this was to have profound consequences later in the war.

As America entered the war, Surcouf was in an American dry dock and undergoing major repairs again and where the American government was keen to get her back to sea and release the dock for more important work.

In Britain, military intelligence officers became aware of communications between the French High Commissioner in Nouméa and the Free French HQ in London. In these, the Commissioner revealed his fear of a Japanese invasion and suggested that Surcouf's presence might provide a valuable deterrence or even practical assistance. It was the golden opportunity that senior staff of the Admiralty were delighted to hear and on Christmas Day, orders were issued so that Surcouf should proceed to Tahiti via the Panama Canal. The British observer aboard Surcouf noted receipt of these orders in his report dated January 16th.

On January 29th, HMS Malabar based in Bermuda, and perhaps fearing another long defect list, suggested that Surcouf should head directly for the canal. This request was ignored and Surcouf sailed from Halifax on February 3rd and arrived in Bermuda on February 7th. As feared, her captain produced a lengthy defect list. One of the electric motors was in desperate need of service and, considering the risk of Surcouf diving out of control again, this was deemed as serious. The dockyard estimated a three month repair time.

The last report from the British Naval Liaison Officer (BNLO) on February 10th 1942 paints a dismal picture of what life aboard this submarine was like. He commended his associates forced to endure the torture with him and how the crew were often drunk and incapable. He revealed the content of a personal conversation with the captain and where the latter revealed inability to recognise some ships as friend or foe. Messages flashed between Malabar and London and where the latter suggested she should go-to-sea irrespective of condition beyond the minimum requirements. The Admiralty knew her presence would not deter the Japanese and one letter even suggested that Surcouf should be paid off and her crew used to supplement the local defence force.

Surcouf had one hundred and fifty rounds of ammunition after which there were no further supplies. In British eyes, the Surcouf was destined to end her days in the Pacific and good riddance!

Repairs delayed Surcoufs departure until 3pm of February 12th and the BNLO and his crew were granted to leave the vessel at Bermuda or Panama but the message did not arrive until after Surcouf had already sailed. She was destined never to reach the Panama Canal and what precisely happened to the Surcouf on that last fatal voyage has remained conjecture ever since. Speculation about sabotage or mutiny was rife at the time but failed to hold up under scrutiny. It seems far more probable, though equally unproven, that she was the victim of a night time collision with a freighter called Thompson Lykes at 10.30pm on February 18th 1942.

At 4.40pm, the previous day, the 6762 ton Thompson Lykes departed from the Cristobal exit of the Panama canal and headed for Cuba. She was 418 feet long and 60 feet wide with a fully loaded draft of 28 feet. On this voyage, she was lightly loaded and drawing 11 feet forward and 27 feet aft. Soon after leaving port, her master, Henry Johnston ordered full speed and the vessel surged ahead at fifteen knots on a heading of 028°.

The ship was just ten months old and owned by the Lykes Brothers Steamship Company of New Orleans. In the wake of Pearl Harbour, the ship had been time-charted by the US Army and was regularly employed to ferry Army cargo. Johnston had been captain of the ship since it was new and the mate, Andrew Thompson, was a very experienced seaman. Most of the crew, by contrast, were conscripts from the US Army 58th Coast Artillery Transport Detachment and many had never been to sea before and because many of the former crew had been drafted into the US Navy.

On February 18th 1942, Johnston wisely chose an experienced seaman for duty in the crow’s nest before retiring to his office behind the bridge. As night fell, external lights remained off while internal lights were shielded. America’s war was only ten weeks old but already merchant vessels had been sunk by U-Boats and Johnston was taking no unnecessary risks. By 7pm, the brief Caribbean twilight gave way to complete darkness and sea conditions began to deteriorate. In response, Johnston ordered a speed reduction to thirteen knots. One hour later, with the weather worsening steadily, Johnston elected to steer a more direct route and the vessel turned to a heading of 022°. He had no warning of other vessels in the area and the rule of radio silence meant he was unable to seek updates or advice. At 9pm, the radio operator received a coded message which changed their current mission and ordered the vessel to sail for Cienfuegos instead. The new course on the gyro was 355°.

All remained quiet until 10.28pm when the helmsman, Atwell, suddenly spotted a white light moving up and down on their right side. He immediately reported it to Thompson who ordered full rudder to port. A short time later, the crows nest telephone rang and the lookout reported seeing a light dead ahead. Thompson, suddenly realising that the unknown vessel was crossing their bows ordered right full rudder but it was too late. Seconds later, the vessel hit something.

Captain Johnston had rushed back onto the bridge and demanded an explanation but before Thompson could reply, there was a loud explosion and a brilliant momentary flare illuminating both sides of the bow. As the flames died away, Private Dohrman Henke, had a fleeting glance of something white in the water and several crewmen heard people calling for help. Johnston and Thompson, blinded by the sudden light, saw nothing and asked Henke what he had seen. The private replied that he thought they had hit a sub and that it had passed down their port side.

Thompson was sent forward with an inspection crew to check the condition of the bow while Johnston ordered a slow turnaround back to the point of impact. Despite the obvious risks, the searchlight was switched on and crewmen lined the rails with orders to look for survivors and/or wreckage. Thompson returned to the bridge and reported that the damage to the bow of the ship was less than first feared and did not threaten the safety of the ship. This news allowed the search to continue and the Thompson Lykes criss-crossed the area several times in search of survivors but none were found.

Neither survivors, bodies or wreckage was found, only a large heavy fuel oil slick. This lack of debris naturally caused the crew to wonder what it was they had hit. They felt certain that it was a vessel of some kind and the helmsman believed that it must have been low in the water else he’d have seen it against the horizon. A few crew members had momentarily seen a long cylindrical shaped object run down the port side of the ship which, when taken together with the above, suggested they had struck a submarine on the surface. Since they had not been notified of friendly vessels in the area, they assumed that the unknown craft was probably a surfaced German U-Boat engaged in recharging her batteries. Captain Johnston broke radio silence and reported the incident to the naval authorities at Cristobal. In reply, the Thompson Lykes was ordered to remain in the vicinity and continue the search.

At 10.45am next morning, the USS Tatnall arrived and both ships were later joined by the destroyer USS Barry. Despite their best efforts, no wreckage or survivors were found and the only sign of the collision remained the oil slick. The Thompson Lykes then departed from the area and returned to Cristobal. She arrived there in the mid afternoon of February 19th and where news that Surcouf was overdue arrived later that day.

Examination of the Thompson Lykes took place shortly afterwards and the American Bureau of Shipping issued their findings on February 25th. They reported that several frames and plates had been distorted and a bottom fuel tank holed. They recommended that, after temporary repairs, the ship should be allowed to proceed to New Orleans for repairs. The damage estimate was $38,000.

Over the following seven months, a bitter wrangle arose between the Free French on one side and the British and American governments on the other. The Free French continually doubted the official reports of the loss and despite subsequent and detailed enquiry concluded that since neither vessel had been showing lights, then this had been the cause of the accident.

So did the Thompson Lykes sink the Surcouf?

Photographs of the damaged bow of Thompson Lykes show a marked twist to starboard and a dent close to the twelve foot mark which suggests that this could have been caused by the deck of the other vessel. There is little damage above this mark and, given the known draught at the bow of eleven feet, we can deduce that the free board (the height above the surface of the water) of the other vessel was very low indeed - perhaps only a few feet at most. This tends to support the crews contention that they had indeed, collided with a submarine.

No other vessels were reported as lost in the area which further points towards the Surcouf as being the victim of this collision. In one report, the BNLO reported that officers in the conning tower of Surcouf often used an unshaded light to see the instruments. Could this have been the flashes of light witnessed by crewmen aboard the Thompson Lykes? In addition, the position of the collision is approximately where one might have expected Surcouf to be.

If the unknown vessel was indeed Surcouf, then it may be that she sank quickly with most of the hull intact and with virtually all contents of that hull trapped inside. The fact that no plates were ripped or torn from the Thompson Lykes suggests that the hull may have remained intact but, with the gun turret and other vital areas flooded, she could have sunk in this state. Such a view is speculation but would explain why no wreckage or survivors were ever found.

The news of her loss and the death of so many brought grief to all who knew them. One of these was Benjamin Britten, the musician and orchestral conductor of note who mourned the loss of his close friend, Roger Burney, the BNLO still aboard the Surcourf when it sank. In time, he penned his musical masterpiece 'war requiem' and dedicated it to the memory of Roger Burney.

Before closing this article; there is factual evidence to show that the Besson aircraft was taken ashore during the time when Surcouf was docked in Britain and had been removed to a nearby dock shed for service. According to records, the Besson aircraft was destroyed there during a bombing raid and could not be replaced. For much of its later career, Surcouf sailed without the aircraft aboard and where the empty hanger was a liability rather than an asset. The big guns were never fired in anger and submarines retreated to a singular role defined in the Royal Navy as 'the silent service' more likely to fire missiles from hidden underwater locations if national security was threatened.