Library Reference Number: 174

Military Aircraft At Sea

Part One: 1900 to 1945

Introduction: The excellent recent submission about ditching in the Indian Ocean by F/O S.D. Turner, R.C.A.F. (Library Ref. 173) reminded me of many things but especially about how few articles received for this web site concern pilots who were compelled to launch from pitching decks of aircraft carriers sailing far from the nearest land or else from crude catapult rails fixed on gun barrels of warships and knowing they could never land back there. Their greatest hope lay with ditching the aircraft and hoping some ship could stop to save them and often knowing that ship Captains were under strict orders not to do so lest they became 'sitting ducks' while their charge was stationary. I'm guessing relatively few made it back and may account for such rarity within our library. It is thus with greatest respect and humility that I present this meagre offering in remembrance to those pilots and crews whose courage and devotion might have shamed Superman in modern times. It's a tribute to those no longer able to speak for themselves. In conjunction with the former article, library ref. 173, our story begins with the decline of the battleship as the primary extension of seapower and where the developments of submarines, wireless and the automotive torpedo changed the World. I apologise in advance for the maritime background during the early parts of this text on an aviation website but please see it for what it is; simply placing the background in appropriate context.

The word 'torpedo' in modern parlance often conjures the mental picture of a pointed cylinder with propellers at the other end. Historically, though, the term properly referred to an electric ray of the fishy variety (and why some submariners refer to automotive torpedoes as fish) or else what would nowadays be described as mines.

Although the desire to place high explosives beneath or beside the hull of a warship goes back centuries, the first link between torpedoes and submersible craft goes back to around 1776 and during the American revolutionary wars. This was when future president George Washington, in conjunction with others, invested in the construction of a one man submarine called ‘Turtle’ and whose design was supposedly capable of affiixng an explosive charge beneath British warships in New York harbour. Part of that process involved drilling with an auger into the hull but by then, British warships were using copper linings and every attempt by the ‘Turtle’ failed. The vessel was eventually lost.

It was the alleged detonation of a torpedo mine beneath the hull of the USS Maine in Havana that largely swayed US public opinion to wage war against Spain in 1898. Spain capitulated and lost many foreign colonies in pursuit of a peaceful settlement even though there is now substantial evidence to suggest the loss of USS Maine was accidental rather than an attack on the ship. The picture on the left shows myself visiting the USS Texas, the last surviving dreadnought battleship in the World now anchored in a bayou close to the Houston Memorial Tower. It was the sister ship of the USS Maine.

It was the alleged detonation of a torpedo mine beneath the hull of the USS Maine in Havana that largely swayed US public opinion to wage war against Spain in 1898. Spain capitulated and lost many foreign colonies in pursuit of a peaceful settlement even though there is now substantial evidence to suggest the loss of USS Maine was accidental rather than an attack on the ship. The picture on the left shows myself visiting the USS Texas, the last surviving dreadnought battleship in the World now anchored in a bayou close to the Houston Memorial Tower. It was the sister ship of the USS Maine.

In 1864, Giovanni Luppis, an Austrian Naval Officer, presented British engineer Robert Whitehead with plans for a floating mine controlled by ropes from the shore and made a contract with him to perfect the weapon. That original plan was quickly put aside and scrapped. Instead, Robert Whitehead delivered the first prototypes of a marine missile and which came to be known as automotive torpedoes in the modern sense.

Early versions of the Whitehead torpedo had limited range and were very unreliable. The first torpedo fired in anger against pirates failed when the intended target was able to sail away at greater speed than the torpedo could attain! Problems of maintaining correct depth were steadily overcome and by 1888, the weapon system was sufficiently perfected to attract the attention of many countries around the World.

In an age when sea power typically implied ‘gunboat diplomacy’ backed by the existence of powerful dreadnought battleships, the automotive torpedo offered a serious alternative shift of power and where such mighty warships, designed and armoured against encounter with similar craft, might actually be vulnerable to attack by less costly, smaller and faster boats or else by submarinesequipped to launch the new weapon. It was the ‘Abdulhamid’, an Ottoman submarine, which became the first to fire a torpedo whilst submerged in 1886.

In an age when sea power typically implied ‘gunboat diplomacy’ backed by the existence of powerful dreadnought battleships, the automotive torpedo offered a serious alternative shift of power and where such mighty warships, designed and armoured against encounter with similar craft, might actually be vulnerable to attack by less costly, smaller and faster boats or else by submarinesequipped to launch the new weapon. It was the ‘Abdulhamid’, an Ottoman submarine, which became the first to fire a torpedo whilst submerged in 1886.

The use of 'spotters' to rely information about enemy movements and preferably from a high place isn't a new concept either. During the Amercian Civil War of 1860-1865, balloons were used on several occassions for this purpose and where the information was relayed by means of flags.

The Japanese attack on Vladivostok (Port Arthur) naval base in 1904 was the opening gambit of a territorial dispute in which the Russians sought to establish an ice-free Pacific base despite political opposition from Japan. It was the first attack in history in which spotters, equipped with wireless technology, were quietly landed in advance of the attack and climbed to the top of the hill separating the anchorage from the sea. Japanese ships, firing over the hill from seaward, were guided by these spotters and several Russian ships were damaged in the attack.

Japanese diplomats had allegedly tried to warn the Russian Court of Czar Nicholas in advance but the actual message was delivered after the attack had taken place and a similar situation would arise decades later concerning the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour. In reponse, the Czar ordered sixty-four year old Admiral Ziconvy Rozhestvensky to lead the powerful Baltic Fleet half-way around the World with a view to settling the issue by force. The long Russian voyage was not without incident and where, at an early stage, British fishermen were fired upon in error and causing a major diplomatic incident. It took ten months for the Russian fleet to reach the Straights of Tsushima near Japan but a lot had happened during that time in Japan.

The Japanese Navy of that time period had styled itself in a manner akin to the British Royal Navy and in just the same way had adopted the dreadnought battleships as the captial warships of its navy. Like Britain, the Japanese had knowledge of how the new automotive torpodo threatened the former belief of invincibility of battleships yet had embraced the new technology by building several smaller torpedo boats. Robert Whitehead's manufacturing facility exported torpedoes on a global basis since the British Naval requirement, as estimated at that time, was insufficient on its own to remain in business. Several were fired in anger during the Chilean Civil War.

In May 1905, the powerful Russian Baltic Fleet, swelled by warships which had escaped from Vladivostok, sailed in the Straights of Tsushima, and most probably unaware of the extensive preparations the Japanese had made well in advance of their arrival. By instance, the wireless radio network had been greatly enhanced to permit sighting and movement of the Russians to be observed and reported more quickly. In addition, the Japanese had conducted extensive live ammunition exercises using a new shell propellant causing far less blinding smoke upon usage. Within ninety days, the Japanese Navy had expended their defence budget normally allotted for the entire year.

The Battle of the Japan Sea, as some called it in the Global Press, contained many strategical parallels to the Battle of Trafalgar fought by British Admiral Horatio Nelson in 1805. As night fell, Admiral Togo, sailing aboard the flagship Mikassa, ordered torpedo boats to move in close under the cover of night while his battleships, some reporting exhaution of ammunition or low fuel, retreated gracefully towards the safety of a harbour. For the Russian Baltic Fleet, it was an inglorious defeat with Admiral Ziconvy Rozhestvensky captured alive next morning aboard a ship he had been compelled to transfer his flag to during the battle. Admiral Togo was hailed as the 'Nelson of the East' in the Global press while the Articles of Surrender were signed and war was concluded.

In 1906, British Admiral ‘Jackie' Fischer proposed a new class of warship for the Royal Navy and which became known as a ‘destroyer’ with both speed and agility inbuilt for use against torpedo boats. In time, these craft would serve far beyond that original remit.

In Britain, and following the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, the Royal Navy had never faced comparable challenge until the the onset of the First World War and where maritime views still favoured the 'big ship and big gun' approach since submarines of the period were slow and incapable of 'sailing with the fleet' and thus of limited value. In Britain, engineers pioneered the idea of a 'steam driven' submarine (I kid you not!) which became officially known as the K-Class but more often referred to unceremoniously as 'mutton boats' by others on account of their appalling loss rate and death toll without ever inflicting a single attack on the enemy. A substantial number of these were wrecked and sunk close to the May Isle, Scotland, during a training exercise which came to be known as the 'Battle of the May Island' albeit without enemy participation of any kind! Later, one of these K-class calamities was adapted to carry a seaplane in a hanger and was redesignated as the M2 and the subject of an article on this website providing greater detail.Click Here to see Branch Library Index Number 215 - for further information on this.

At the start of World War One, Germany had twenty-nine submarines and even when deemed absent from some theatres of war, the fear of possible presence resulted in caution. At the Gallipoli invasion, Allied warships could have assisted the invasion via heavy shell bombardment but stood back out of range and fearing U-Boat attack. Although several notable incidents involving 'Unterseeboots' or U-Boats did occur during World War One, their involvement had far less impact than in World War Two.

Similar comment can be applied to aircraft during this period and where the most obvious application began with flights over enemy trenches while armed with little more than a camera. It was even said that where two pilots of opposing forces met in the early stages of the war, they might actually wave to each other in chivalrous courtesy and accept both were doing a similar job.

Of course, as the pressure mounted, more pilots took rifles and revolvers into the skies with the intent of killing the opposition. In a very short space of time, this led to aircraft being fitted with guns. It had began with pilots carrying shotguns and pistols but ultimately included fitment of machine guns to the aircraft. In terms of technology, the Focher Interupter Gear proved outstanding and permitted German pilots to aim and fire directly at their enemy with bullets passing through the brief period of time when the propellor was absent. The German tri-plane design and deployment proved superior to Allied counterparts while aerial exploits of the Manfred Von Richthofen better known as the 'Red Baron' captured the imagination and global news headlines.

It remains uncertain as regards the exact manner of his death on 21st April 1918 near Amiens. It was planned as his last mission before retirement but it seems entirely possible that he was shot by groundfire from an Aussie occupied position whilst at low altitude and in pursuit of an Allied plane. He was buried with full reverence by the Allied forces.

In January 1916, Admiral Reinhard Scheer of the German Kaiserliche Marine proposed a plan to draw Royal Navy warships into a trap whilst breaking the British blockade on German mercantile shipping. The plan was to deploy five modern battle cruisers under the command of Vice-Admiral Franz Hipper and where the likely reaction of Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty would be to intercept them in an effort to keep them distant from British merchant sea-lanes. German submarines were to form a picket line along the route most likely to be taken by the British ships. In addition, the plan was meant to draw Beatty’s squadron into the reach of the main German fleet and where a substantial portion of the Royal Navy would be outgunned and destroyed.

Almost as soon as the German ships left port, Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty, based at Rosyth in Scotland, reacted more swiftly than predicted and took his fleet to sea while the German plan suffered crucial delays. British interception of radio traffic suggested that a major German fleet operation was underway so Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, based at Scapa Flow in Orkney, sailed with the British Grand Fleet to rendezvous with Beatty’s squadron. The German delays now played a part in that the submarines had reached their assigned positions too late and often at the limits of their endurance. By the time, German submarines were in place, the British Royal Navy had already passed beyond these positions and opportunities had been missed.

Beatty’s squadron of ships caught up with Hipper’s more quickly than the Germans had expected and the first engagement took place on the afternoon of May 31st. In this first part of the battle, Hipper almost succeeded in luring Beatty into the trap but as Beatty sighted the German battleships moving in, he turned his squadron away in the direction of the British Grand Fleet. By the time, Beatty had extricated his squadron from the situation; two of his battle cruisers had been sunk.

Between six-thirty and eight-thirty that evening, the German fleet of ninety-nine vessels were pitched against one hundred and fifty-one of the Royal Navy on two occasions and where Jellicoe and Beatty did their best to stop the German fleet from retreating back to their harbours but failed to prevent their escape. In that effort, the British lost a further twelve ships while the Germans lost eleven in total. Twice as many British sailors died compared to that of Germany.

Although the British lost more ships, and prompted Betty's comment, "There's something bloody wrong with our ships today", both sides claimed victory although the press was scathing about how the British Navy should have pressed forward. It remains as a contentious issue, but with night upon them, the fear of encountering torpedo boats (as had happened at Tsushima) may have been an important consideration when Admiral Jellicoe wisely decided to withdraw the British fleet from the area.

Within the footnotes of this battle, however, is a report of how a British aircraft fitted with floats was successfully lowered into the sea from the seaplane tender HMS Engadene and flew high above the battle zone yet unable to report what was observed due to radio equipment failure. What might have been vital strategically important information from this source was never reported to Jellicoe or Beatty.

As stated, both sides claimed victory and with some justification on both sides but the essential verdict lay in the future. Neither had delivered the ‘knock out’ blow that Trafalgar had been but despite some later German attempts to redress the British Naval superiority, Germany was ultimately compelled towards ‘unrestricted submarine warfare’ and began a naval campaign on that basis.

It’s often mistakenly said that the sinking of the British liner RMS Lusitania in 1915 by a German U-Boat eleven miles from the southern coast of Ireland and claiming nearly twelve hundred lives (128 of them were US citizens) was the primary motivation for the United States of America to enter the war on the Allied side. It wasn’t the primary reason yet doubtless an influential factor when British Intelligence decoded the Zimmermann Telegram addressed to the Government of Mexico and inviting them to make war with the United States with support from Germany. In this agreement, Germany would provide the necessary supplies and reward participation by granting all territories formerly held to be Mexican before the events of 1836 and in which major parts of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona would be returned to their control if successful. In addition, Mexico was urged to broker deals with the Japananese Empire.

For the twenty-eighth President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, and in a nation still reeling from the catastrophe of Civil War just one generation before, the Zimmermann Telegram must have come as a total shock and nightmare. Wilkson had tried so very hard to keep US involvement in the war within the bounds of neutrality but the Zimmermann Telegram changed everything. The declaration of ‘Unrestricted submarine warfare’ by Germany made the postion of neutrality untennable. On the 6th of April 1917, Woodrow Wilson reluctantly declared war with Germany.

Ever since the American Civil War, and where the shocking casualty rate had become public knowledge; each and every President of the US has sought means to ensure that future wars would never be fought on American soil and where aircraft carriers and task forces are a crucial core of that ‘forward defence’ strategy existing unto current times.

On the eleventh of November 1918, and in a rail carriage located in a side rail area at Compiėgne in France, World War One was officially concluded on paper albeit with some parts of the war lasting some time longer. The signing of surrender by German forces during that first conflict at the ‘eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month’ remains central to the ‘Remembrance Day’ celebration and where mankind ought to have learned many lessons yet failed to in so many ways.

In 1922, French troops occupied the German Ruhr industrial area in protest that the reparation payments for causing the war had not been met. Their action had led to a massive devaluation of the German currency and where the proverbial barrow load of coins might buy a loaf of bread came into being! It was amid such poverty and despair that a new force evolved and was permitted to assume political power in Germany and it became the era in which public works like the autobahns, bridges, dams and much more were introduced to ensure employment and income. Cellars commonly built in German houses often became manufacturing and production workshops delivering component parts for larger assembly into factories and explains why it was so hard to defeat Germany during the earliest stages of the Second World War.

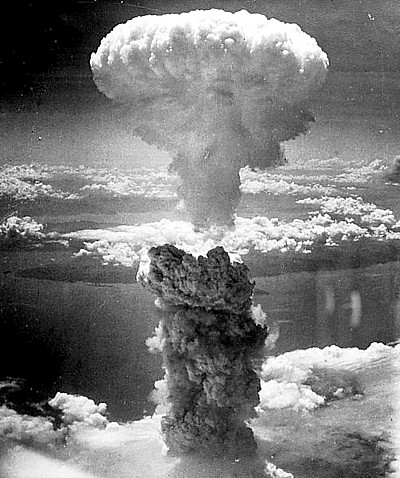

In 1933, Adolf Hitler became leader of Germany and where his efforts to get everyone back to work and restoring the German economy included expansion of the armed forces and where parity in warships came closer to that of the Royal Navy than had been the case in World War One. His economic measures resulted in the most industrially productive period of German history and where small cellar workshops in many homes manufactured components for a wide range of industries. It's sobering to realise that if the Second World War had begun some five years later then Germany might have won it with comparative ease! By then, they might have had an aircraft carrier at sea, improved markedly upon their submarine technology, introduced heavy duty long range bomber aircraft to their air force and perfected long range missile and atomic bomb technology!

On 22nd June 1940, the same rail carriage and location at Compiėgne in France was used to humble the French nation as French forces surrendered to their German counterparts. France was split in two parts with the North being governed directly from Berlin by occupation while the South came to be ruled by Vichy government working in alliance with Germany. The major problem concerning the powerful French fleet was made difficult since Admiral Francious Darlan had received no clear instruction prior to the surrender being signed.

With most of the fleet in harbour at Toulon in Southern France, he deemed it wise to take the fleet across the Mediterranean Sea to the port of Mers-El-Kebir near Oran in French Algeria. Despite transmitting reassurances to the British government that the fleet would remain independent and neutral, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was less trusting and afraid that Germany would seek to acquire these and other French warships located elsewhere. In a lengthy ultimatim offering many acceptable alternatives, and including one favoured by Darlan himself - that of internment with the US governmentfor the duration of the war - was rejected by Admiral Marcel-Bruno Gensoul commanding the fleet at Mers-El-Kebir. Darlan was never shown the full text of the ultimatim and would most likely have favoured the US internment option. In the event, it became clear that Gensoul was reluctant to accept any of the kinder options and even before the negotiations became bogged down, Force H under the command of Vice Admiral James Sommerville, launched Fairey Swordfish and Blackburn Skua aircraft (No 800 Fleet Air Am Squadron) to drop magnetic mines along the route that French vessels would have to take on leaving port. The French countered with Curtiss H-75 aircraft and one of the British Skuas was shot down and crashed in the sea. The two crewmen became the only British casualties of the battle.

On the afternoon of 3rd July 1940, Operation Catapult was undertaken with the battleships HMS Valiant and HMS Resolution plus the battle cruiser HMS Hood firing on the French warships. On the third salvo, and first shell to hit a French warship, the magazine aboard the Bretagne exploded and the ship rapidly sank taking nine hundred and sevety-seven crewmen with it. The French battleships Provence, Dunkerque and the destroyer Mogador were deliberately run aground after receiving damage. The French battleship Strasbourg and four destroyers managed to escape from the port but they were pursued an attacked by Fairey Swordsfish aircraft with bombs launched from HMS Ark Royal but to no great effect. Two of the British planes were shot down by anti-aircraft fire but their crews were rescued by HMS Wrestler.

Another British attempt to bomb the Strasbourg took place shortly before nine o'clock in the evening but failed. With night approaching Vice Admiral Sir James Sommerville decided his forces were ill-equipped for a nighttime engagement and called off the pursuit. The Strasbourg reached Toulon next day and the French Armee de l'Air (French Air Force) attacked the British Naval Port at Gibralter but the damage caused was minimal. On that same day, 4th July, a British submarine, HMS Pandora, sank the French gunboat Rigault de Genouilly (pictured) close to the coast of Algeria. That night, aircraft of the Armee de l'Air (French Air Force) attacked the British Naval Base at Gibralter but most bombs fell into the sea and damage was minimal.

Another British attempt to bomb the Strasbourg took place shortly before nine o'clock in the evening but failed. With night approaching Vice Admiral Sir James Sommerville decided his forces were ill-equipped for a nighttime engagement and called off the pursuit. The Strasbourg reached Toulon next day and the French Armee de l'Air (French Air Force) attacked the British Naval Port at Gibralter but the damage caused was minimal. On that same day, 4th July, a British submarine, HMS Pandora, sank the French gunboat Rigault de Genouilly (pictured) close to the coast of Algeria. That night, aircraft of the Armee de l'Air (French Air Force) attacked the British Naval Base at Gibralter but most bombs fell into the sea and damage was minimal.

On the morning of 6th July, 1940, Fairey Swordfish launched from Ark Royal returned to Mers-El-Kebir following a British assessment that the battleships Dunkerque and Provence as repairable and hence still a threat. During this renewed attack, one air launched torpedo hit the patrol boat Terre-Neuve, which was moored alongside Dunkerque and was carrying a supply of depth charges. Terre-Neuve sank in seconds but its cargo of depth charges exploded and inflicted major damage to the Dunkerque. The Dunkerque, Provence and Mogador were later partially repaired and sailed back to Toulon.

On the 8th July, Swordfish aircraft launched from HMS Hermes attacked the French battleship Richelieu at Dakar in Senegal. One air launched torpedo scored a direct hit and damaged the ship.

French ships in Alexandria under command of Admiral Rene-Emile Godfroy, including the old battleship Lorraine and four cruisers, were blockaded by the British in port from 3rd July 1940 and offered the same terms as at Mers-el-Kebir. After delicate negotiations, conducted on the part of the British by Admiral Cunningham, the French Admiral agreed on the 7th July to disarm his fleet and stay in port until the end of the war. They stayed there until they eventually joined with the Allied cause in 1943.

Naturally, there were several French warships who sailed towards British ports as refugees during the fall of France in 1940 and all were boarded and interred on the 3rd July. Most were old battleships or torpedo boats but it did include the largest submarine in the World at that time. The story of the Surcouf and which had an aircraft hanger, is more fully described elsewhere on this website. Click for more information about Surcouf!

On 27 November 1942, the Germans attempted to capture the French fleet based at Toulon but all ships of any military value were scuttled by the French before the arrival of German troops, and notably including the Dunkerque and Strasbourg. For many in the French Navy this was a final proof that there had never been a question of their ships ending up in German hands and that the British action at Mers-el-Kebir had been an unnecessary. Within days Winston Churchill received a letter from Admiral Darlan, in which he wrote; "Prime Minister you said to me 'I hope you will never surrender the fleet'. I replied, "There is no question of doing so". It seems to me you did not believe my word. The destruction of the fleet at Toulon has just proved that I was right."

Before closing this section, and in this author's personal opinion, it will always remain contentious whether the Battle of Mers-El-Kebir should have been fought at all. A similar ultimatum presented at the port of Alexandria in Egypt had been accepted with better grace and hence no need for a battle there. It's public knowledge that Gensoul was upset that a relatively junior officer had been sent to conduct negotiations on behalf of the British yet for entirely practical reasons. Commander Cedric Holland of HMS Ark Royal was a fluent French language speaker. Gensoul sent his lieutenant as a response and where multiple causes of misunderstanding could have taken place. Nearly fourteen hundred French lives were lost in the action and far more than those lost at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415. Consequently, it's not surprising to learn that relationships between General Charles de Gaulle as leader of the Free French Forces and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill were often strained. Even in the post-war era, and as the initial Benelux union prospered into the European Economic Community, it was French President Charles de Gualle who successfully vetoed British entry on several occassions right up until his death in 1970. Vice Admiral Sir James Sommerville later wrote down his regrets and qualms concerning the action taken at Mers-El-Kebir.

The sudden collapse of French forces so early during World War Two had important implications as regards survival in Britain. The British Army had been compelled to abandon huge quantities of weapons and stores as they retreated from Dunkirk and Germany now had a long and convenient coastline permitting direct access to the Atlantic Ocean. In the Global Press, it seemed certain that Britain would be next on the list of Adolf Hitler's conquests as Germany prepared for 'Operation Sea Lion' in which German forces would cross the Channel and invade Southern England. Before the invasion could proceed, however, Germany needed aerial supremacy to ensure the invasion stood a xhance of success and the Luftwaffe became assigned to this task in the summer and autumn of 1940. For many days, the Luftwaffe attacked Royal Air Force bases and were met by British fighter aircraft in a series of aerial conflicts that has become known as the 'Battle Of Britain'.

The British started this conflict with nearly two thousand serviceable aircraft but losses were appalling with nearly sixteen hundred of these destroyed. Five hundred and forty-four aircrews were killed and over four hundred wounded. On the German side, the losses were even worse with two thousand five hundred and fifty aircraft before the conflict and losing one thousand eight hundred and eight seven aircraft and nearly two thousand seven hundred aircrew in the Battle.

It became a close run thing with the RAF initially on the losing side and despite usage of pilots from many nations contributing to the defence effort but at a crucial stage, the Luftwaffe changed its tactics and began bombing London rather than the British airfields and this switch allowed many rapid repairs to be made to these airfields. Germany had no long range heavy bombers and much of their mission over Southern England had to be accomplished without fighter escort and thus making them more vulnerable to attack. Nearly one thousand German aircrew were captured during the battle. In a matter of days, the Battle switched in favour of the British and the decision to 'postpone' Operation Sea Lion was taken in the belief that aerial supremacy over British soil could not be acheived at that time. Germany never got a second chance to resurrect the invasion plan!

"Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few!" observed Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Ever since that time, participating pilots on the British side have been referred to as 'the few' with reverence and respect. Their effort stopped the German advance in its tracks but the question of long term survival had not been determined.

Even in advance of the Operation Sea Lion proposal, the Kreigsmarine had deployed a large number of Schnelleboot or 'fast patrol boat' which became known as E for Enemy boats in English. The typical E-Boat of German design was capable of speeds exceeding forty knots and could typically sail for about nine hundred nautical miles at about 30 knots. Made of wood and pwered by three Daimler diesal engines, the vessels carried four torpedoes and were fitted with two torpedo launch tubes and a variety of machine guns. Many had three rudders with the outer two mounted at an angle and when running at speed, this had the effect of elevating the stern and reducing the wash by a significant factor and thus making it harder to spot their movement in poor light. During the Second World War, E-Boats were extensively used to lay mines and where their contribution to shipping losses exceeded three hundred and fifty thousand tons. To combat this menance, the British initially armed and modified existing boats but these had the serious drawback of petrol driven engines and were more likely to come off worst in an encounter with an E-Boat.

The first clash of British and German warships in War Two took place in the Southern hemisphere and ironically close to where former German Admiral Graf Maxmilian Von Spee had taken his First World War One squadron after their victory over British Admiral Cradock at Coronel near the Chilean coast on 1st November 1914. Graf Spee had taken his small fleet into Valparaiso and where the enthusiatic audience adorned him with flowers. He's reputed to have said that they would look nice on his grave and in sure knowledge the Royal Navy would avenge Coronel. What he and Craddock hadn't known, was that Sea Lord Winston Churchill had already despatched ships to support defence of the Falkland Isles. The British Fleet had arrived just two days after Cradock had sailed for the fateful encounter at Coronel. Graf Spee had sailed for Port Stanley in the Falkland Isles with intent to attack and possibly unaware that HMS Glasgow had survived Coronel and had headed for Port Stanley and now ready to resume warfare with the newly arrived additional support. The German fleet had been annihilated and Graf Spee and his two sons died in the action.

The first clash of British and German warships in War Two took place in the Southern hemisphere and ironically close to where former German Admiral Graf Maxmilian Von Spee had taken his First World War One squadron after their victory over British Admiral Cradock at Coronel near the Chilean coast on 1st November 1914. Graf Spee had taken his small fleet into Valparaiso and where the enthusiatic audience adorned him with flowers. He's reputed to have said that they would look nice on his grave and in sure knowledge the Royal Navy would avenge Coronel. What he and Craddock hadn't known, was that Sea Lord Winston Churchill had already despatched ships to support defence of the Falkland Isles. The British Fleet had arrived just two days after Cradock had sailed for the fateful encounter at Coronel. Graf Spee had sailed for Port Stanley in the Falkland Isles with intent to attack and possibly unaware that HMS Glasgow had survived Coronel and had headed for Port Stanley and now ready to resume warfare with the newly arrived additional support. The German fleet had been annihilated and Graf Spee and his two sons died in the action.

Approximately a quarter century later, the powerful 'pocket battleship' bearing his name began 'commerce raids' against British shipping in September 1939 and whilst under the command of Hans Langdorf. The British response was to send ships to 'seek out and destroy' the raider. One group comprising HMS Exeter, HMS Ajax and HMS Achillies (the latter of New Zealand Group)found their quarry on the early morning of 13th December 1939 and where HMS Exeter bore the brunt of the armed exhange and was forced to retire to the Falklands Isles for repairs. Unknown at that time, one of Exeter's shells had inflicted severe damage on the Graf Spee fuel system and Langsdorff steered the battleship into the neutral port of Montivideo to effect repairs.

What followed was largely a wrangle in which the British diplomatic representation proved superior. Langsdorff was granted seventy-two hours in which to repair his vessel then leave port but that proved to be impossible. At the same time, global news reported that British warships were assembling and ready to meet with that deadline. Landsdorf chose to have his crew interred in neutral Urequay before scuttling his ship in deep water. British requests to examime the wreck soon afterwards and with particular interest in the aiming systems were refused on the grounds of maintaining national neutrality.

It's often remarked how the map of Italy looks like a boot and for the purposes of this article, one can say that between the toe and heel of boot lies the Italian Naval Base of Taranto. Following the action at Mers-El-Kebir as described above, the powerful Italian battleships based at Taranto represented a major threat in the the Mediterranean Sea and a daring British plan to attack these ships in port was undertaken on the night of 11-12 November 1940. Operation Judgement, as it was called, would change the role of aviation at sea forever and have profound implications for the future!

Originally planned to take place in October 1940 and including HMS Eagle as part of the task force, accidents and technical difficulties eventually excluded HMS Eagle from participation and where the newer HMS Illustrious was employed as the solitary fleet carrier for the operation and using five aircraft transferred from HMS Eagle. The complete naval task force, commanded by Rear Admiral Lyster, who had authored the plan of attack on Taranto, consisted of Illustrious, two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and four destroyers. Their were doubts about his plan since the twenty-four Swordfish (813,815 and 824 Naval Air Squadrons) were too few in number to accomplish the desired result. In addition, Taranto Harbour was and is about twelve metres (39 feet) deep and there was a real possibility that any air launched torpedoes would merely ground on the seabed. It was also known that the anti-aircraft defences at Taranto were formidle and a loss rate of fifty per cent was predicted.

In what became the first ever all-aircraft ship-to-ship naval attack in history, twelve modified Swordfish biplanes with armed with torpedoes and a drum of wire affixed to the nose of each aircraft. From this drum, a wire was affixed to the nose of the torpedoes and where, once launched from the aircraft would cause sufficient drag resulting the torpedo striking the sea on a more level plane and thus less likely to dive too deep and hit the seabed. The other twelve Swordfish were armed with bombs and flares; the latter as a means to deceive the enemy defenders.

In advance of the attack, RAF No. 431 General Reconnaissance Flight flew Martin Maryland bombers on reconnaissance flights from Malta to establish details of the target and the sudden and unexpected presence of barrage ballons caused alterations to the original plan. On the night of 11th November, a Shorts Sunderland was employed to determine whether the Italian fleet was still in port and just as the Royal Navy fleet lay close to the Island of Cephalonia and about two hundred miles (170 nautical miles or 310 kilometres) from Taranto. Italy had no radar systems of any kind and thus no effective measures to prevent this information gathering process no means to detect advance movement of aircraft towards their shores.

The first wave comprised twelve aircraft, six with torpedoes and six with bombs. They were launched from HMS Illustrious shortly before 21:00 hours with the second wave departing the aircraft carrier some ninety minutes later. One aircraft of the first wave returned early fuel tank problems while another was delayed after a taxiing accident requiring some rapid repair work.

The attack began at 22:58 with the bombers targeting oil storage facilities while the torpedo aircraft endured mixed fortunes with some notable successes with hits on the battleships 'Caio Duilio', 'Littorio'and 'Conti di Cavour' yet leaving the 'Andrea Andoria' unscathed despite their best efforts. The last plane of the raid returned to the Illustrious at 02:39 in the morning. Two aircraft had been shot down during the raid with one crew being crew being captured while the other did not survive.

The 'Caio Duilio' was deliberately run aground to save her from sinking; a similar decision was applied to the 'Littorio' where three torpodoes had created massive damage and where subsequent reconnaisence showed her bows submerged by the following morning. The 'Conti di Cavour' came off worst with a 12x8 metre hole blasted into the hull and where all subsequent attempts to save the ship failed. The wreck was salvaged later and partially restored but never completed. Damage to the 'Caio Duilio' and 'Littorio' was repaired within six months but by then the overall war pattern had changed markedly and had illustrated how twenty-one aircraft had changed the course of history and where Italy had lost fifty per cent of its capital warships in one night!

Next morning, many Italian ships undamaged in the attack were ordered to Naples in an immediate 'knee jerk' response and ahead of any repetition already being planned by Admiral Cunningham of the Royal Navy but ultimately prevented by adverse weather conditions. In that respect, the doubts about having too few aircraft had been proven.

According to Admiral Cunningham "Taranto, and the night of November 11–12, 1940, should be remembered for ever as having shown once and for all that in the Fleet Air Arm, the Navy has its most devastating weapon."

In time, his observation would become truth but in another singular event located on the other side of the World and more than a year later where the target was also a harbour of modest depth measuring thirteen metres (42 feet)deep and where similar techniques were applied and copied but on a more grandeous scale. On 7th December 1941, the combined aircraft forces of four Japanese aircraft carriers would repeat similar tactics and apply them to the devastating attack on US Navy ships based at Pearl Harbour.

It was the day when Japanese ambassadors failed to deliver their declaration of war ahead of the raid and in curiously similar fashion as that which had taken place ahead of the Japanese raid on Vladivostok so many years earlier. It was the day when the Japanese Navy folowed similar plans to that enacted at Taranto and where the war became Global for a second time! More on this later in this text!

In the opening stages of the solitary continuous action of the entire war, Germany held the 'ace cards' and where the principal weakness of the British war effort was reliant upon mercantile trade sailing across a U-Boat infested Atlantic Ocean. To many minds, this might suggest a one-way traffic system but that wasn't always true. Consolidated's Liberator bomber aircraft serving with the USAAF were fitted with undercarriage gear manufactured in Glasgow!

In the immediate period preceeding World War Two, Germany had manufactured sixteen long range aircraft with the expectation of serving as trans-Atlantic passenger aircraft. Almost immediately as war broke out, these aircraft were stripped of all finery and fitted with additional fuel tanks to provide even greater range and capability in their new assigned role to search for British convoys and to rely such information back to German Admiral Karl Donitz commanding U-Boat operations in the Atlantic. In this way, the 'Condor' aircraft became the eyes of the U-Boat fleet and where intercept courses were relayed to U-Boat Commanders.

The surrender of France made this proposition much easier to undertake with submarine pens being built at many ports along the long French coastline facing the Atlantic. Such pens were built to withstand regular bombing from aircraft and provided safe shelter for U-Boats during times of repair and resupply.

.jpg) By contrast, British and Commonwealth defence of this vital supply line began with the purchase of outdated warships from the United States to defend convoys whilst woefully lacking equipment suitable for the task. In some cases, guns couldn't elevate high enough for use as anti-aircraft guns and had obviously been designed with ship-to-ship encounters in mind. It wasn't as if the issue of air cover hadn't received sufficient thought during the intervening years between the wars because it had clearly been given a degree of priority.

By contrast, British and Commonwealth defence of this vital supply line began with the purchase of outdated warships from the United States to defend convoys whilst woefully lacking equipment suitable for the task. In some cases, guns couldn't elevate high enough for use as anti-aircraft guns and had obviously been designed with ship-to-ship encounters in mind. It wasn't as if the issue of air cover hadn't received sufficient thought during the intervening years between the wars because it had clearly been given a degree of priority.

Even in the closing stages of World War One, an Italian liner originally laid down as the 'Conte Rosso' had been purchased by the Royal Navy and heavily modified to become the first dedicated aircraft carrier in the World. HMS Argus (pictured) provided many lessons andbecame the prototype of almost all aircraft carriers built since. In subsequent years, the Royal Navy invested heavily in aircraft carriers but when resumption of the 'auld conflict' resumed in 1939, they were insufficient in number and many of the aircraft being used were old and outdated. None could be spared for convoy protection duties.

Consequently, and in the early stages of World War Two, supply convoys typically assembled at Halifax in Newfoundland and began their eastward voyage accompanied by Lockheed Hudsons of the Canadian Air Force. Their counterpart, in the Eastern Atlantic were Sunderland Flying Boats typically launching from bases in Scotland yet neither having the range and ability to ensure complete air cover over the mid-Atlantic. This crucial gap of air cover became known as 'U-Boat Alley' and where the risk to mercantile shipping was greatest. In later years, 'Former Naval Person', British Prime Minister Winston Churchill conceded that the 'U-Boat menance' worried him more than all other challenges he had encountered during the war.

From a German U-Boat crew perspective, this early stage of the war was described as the 'happy time' and where the preferred method of attack remained similar to that of World War One and largely because the technologies were similar. On the surface, U-Boats were powered by diesal engines and capable of considerable speed and maneouverability but differing conditions applied when the U-Boat was submerged and reliant on the limited abilities and capacities of electric propulsion. In stark contrast to modern nuclear submarines whose submerged capabilities often exceed that of their surfaced profile, the U-Boats of World War Two can best be described as surface vessels with the ability to submerge if required to do so. It's an important distinction and explains why so many U-Boat Captains preferred the method of getting in close at periscope depth, usually under the cover of night, then surfacing before commencing their attack and hoping their small surfaced profile would not be observed. For the most part then, U-Boats undertook their voyages on the surface and where aerial cover represented a potential threat. There are examples related on this website where submarine versus aircraft encounters took place

Closing 'U-Boat Alley' became a priority for the British of necessity and meant taking aircraft to sea and where the aircraft carrier became a very British invention albeit copied by others. Almost every major innovation concerning aircraft carriers, like the angled flight deck, the steam catapult and the launch ramp has British origins.

In World War Two, the initial response was to equip some ships with an ability to launch aircraft from ramps but where recovery was problamatical rather than certain. Ditching the aircraft into the sea was risky in itself when the fuel was expended but also at a time when convoy captains were under strict orders not to stop lest their vessel became a 'sitting duck' and an easy target for U-Boat attack. It seems highly likely that some pilots did survive the initial ditching only to become abandoned by the crews they had been protecting! "Loose Lips Sink Ships" was a common expression and undertaking during the war and where the mysterious loss of the aircraft carrier 'HMS Dasher' illustrates this perfectly. It returned to port after reporting engine difficulties, then blew up and sank amid mysterious circumstances near the Isle of Arran. The cause remains conjectural but it was many years before anyone spoke about it lest the Germans heard about it.

As the war progressed, 'U-Boat Alley' became narrower as larger merchant ships were hastily fitted with flight decks and equipped with a 'Seafire' variant of the Spitfire aircraft. Condors could no longer command safe observation of the mid-Atlantic skies and the U-Boat menace began to diminish as a consequence. The introduction of ASDIC, a forerunner to modern sonar sounding technologies more commonly applied in modern times for maritime research of objects underwater, became a useful tool for detecting submerged U-Boats while RADAR systems became sufficiently viable as to detect submarine conning towers. The old age method of dropping drums of explosive Amatol preset to detonate at preset depths gave way to smaller charges launched in specific patterns from a rack called 'hedgehog' on account of the 'prickly' launcher mechanism left behind on deck. and exemplars of technological progression.

Best estimates of the U-Boat campaign waged by Germany suggest some two thousand eight hundred and twenty five merchant vessels were lost to U Boats in World War Two. One hundred and seventy-five warships can be added to this loss figure.

In so many ways, the Battle of the Atlantic became one of advancing techologies and countermeasures with the U-Boat eventually coming off worst. During the closing stages of World War Two, the survival chances of a U-Boat crew came close to zero. Aircraft fitted with RADAR and Leigh Lights could get in close before illuminating their targets at night. 'Highball' spinning variants of the 'Dam Buster' bombs were used on some Mosquito aircraft to attack submarines. Barnes Wallis, genius and inventor of the 'dam buster' bombs also designed 'Tallboy' bombs that could not be dropped from normal height on account of their sheer weight; but proved excellent destroyers of the armoured German submarine pens in France!

For a brief time there was conflict of policy between Britain and America (introduced to the war on the Allied side in December 1941 after the attack on Pearl harbour) as to how the U-Boat threat should be handled. For Britain, protection of the convoy was the primal motivation whilst US policy was more agressive and demanded a hunter-killer approach to seek destruction of U-Boats. Neither policy could be considered as wrong and where application of both led to horrendous losses of German submariners. It's commonly accepted that around seven hundred and seventy U-Boats were sunk in the latter stages of the war and equating to around thirty-eight thousand submariners!

Although not strictly part of the Atlantic Battle, convoys from Britain to Murmansk in Russia faced similar threats and employed similar advances in technology to gain the upper hand. The supplies they delivered to Russia were vital and the result at Battle of Stalingrad might never have been possible without these supplies.

When the war in Europe ended in 1945, the Allies were shocked to discover the extent to which the Germans had advanced submarine technology and where a new generation of U-Boats had been in construction but never deployed. Again, this represents another example of German plans which came too late to affect the outcome of the war. It leavers one wondering what might have happened if the war had taken place just a few years later than it did!

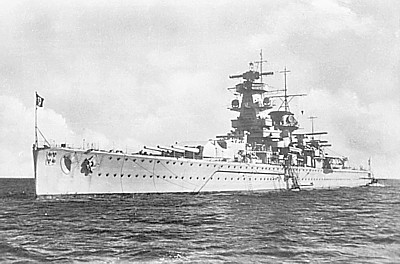

In the wake of World War One, a negotiated settlement, known as the 'Washington Naval Treaty', was reached in early 1922 between the United States, Britain, France, Italy and Japan as a means to reduce arms escalation concerning the building of aircraft carriers, battleships and cruisers. Although lesser vessels weren't specifically included by class, a limit of 10,000 tons was desireable. By 1934, however, Japan and Italy, had abandoned their commitment to this treaty and thus rendering the whole treaty untenable. In Japan, two battleships already in building were hastily redesigned to become aircraft carriers and more began to be built in the 1930s. Two of these carriers, the IJN Hiryū and IJN Akagi (pictured), remain unique in having port side island structures. With limitations in place by International Treaty, the first generation of Japanese aircraft carriers were small but then blossomed in size as the treaty was abandoned. Consequently, and perhaps because of the treaty, Japan chose to operate several aircraft carriers together in order to maximise the strike power of its aircraft carriers during World War Two.

In the wake of World War One, a negotiated settlement, known as the 'Washington Naval Treaty', was reached in early 1922 between the United States, Britain, France, Italy and Japan as a means to reduce arms escalation concerning the building of aircraft carriers, battleships and cruisers. Although lesser vessels weren't specifically included by class, a limit of 10,000 tons was desireable. By 1934, however, Japan and Italy, had abandoned their commitment to this treaty and thus rendering the whole treaty untenable. In Japan, two battleships already in building were hastily redesigned to become aircraft carriers and more began to be built in the 1930s. Two of these carriers, the IJN Hiryū and IJN Akagi (pictured), remain unique in having port side island structures. With limitations in place by International Treaty, the first generation of Japanese aircraft carriers were small but then blossomed in size as the treaty was abandoned. Consequently, and perhaps because of the treaty, Japan chose to operate several aircraft carriers together in order to maximise the strike power of its aircraft carriers during World War Two.

The decision to attack Pearl Harbour arose due to political difficulties between Tokyo and Washington in the preceding months and where some degree of brinkmanship and provocation must be awarded to the US government before the attack took place. When the response came, it wasn't quite what the US government had expected!

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Commander in Chief of the Japanese Navy, had been educated at Harvard University in the USA and when the order was given to attack forces of the United States, he had expressed the viewpoint that an attack of massive scale would be necessary and where it might take a year for American industries to respond with sufficient resources to challenge them. His biggest fear concerned the existence of American aircraft carriers normally based at Pearl Harbour in Hawaii and the initial plan was drawn with these specific targets in mind rather than the battleships also stationed there.

From the outset, there were many aspects of the plan akin to the raid successfuly executed by the British on the Italian Naval Base in Taranto roughly a year earlier but with an obvious need for more aircraft. Ultimately, six aircraft carriers (Akagi, Kaga, Sōryū, Hiryū, Shokaku and Zuikaku) were despatched in secret towards Pearl Harbour with the collective ability to launch four hundred and eight aircraft with three hundred and sixty forming the attack squadrons in two waves while the remainder were retained for the crucial air defence role above the fleet. In common with Taranto, there was no effective radar early warning although some stations deemed as experimental had been set up and were some of the first to report approaching aircraft. In addition, British Intelligence sources, having broken Japanese Naval Cyphers, had warned of Japanese attack but American suspicion of British interests had limited distribution of this alert.

What followed on that Sunday morning was thus an attack delivered with complete surprise and to major effect on all vessels parked along 'battleship row' and killing thousands of US sailors and virtually destroying the US battleship fleet yet lacking the essential targets sought most by the Japanese Admiral. The final aerial scout missions had failed to discover the whereabouts of the principal aircraft carrier targets namely USS Enterpise, USS Lexington and USS Saratoga' and where they were crucially absent and 'at sea' yet Yamamoto commanded the raid to proceed and thus inviting a reluctant United States of America into Global war for a second time. In modern times, there is a special memorial in Pearl Harbour and dedicated to the three thousand or more souls lost aboard the USS Arizona and tribute to many more killed on neighbouring ships. Vengenge, as Admiral Yamamoto had predicted, would take time to evolve, but before then, Japanese aims of territorial expansion could be acheived in great measure with minimal opposition.

Three days later, on 10th December 1941, the battleships HMS Repulse and HMS Prince of Wales were attacked as part of Force Z sailing from Singapore and sunk by Japanese aircraft and thus proving once again the vulnerability of warships to aerial attack. In so many ways, the era of battleship supremacy had ended on that day! On 15th February 1942, British forces in Singapore surrendered to the Japanese; an event described by Winston Churchill as "the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history".

In the Pacific theatre of the Second World War, Japanese advances were rapid and directly led against former colonial territories allegedly owned and controlled by European interests. When pitched against such interests, European forces seemed woefully inadequate and unable to defend such claims.

Like other nations originally signatory to the Washington Naval Treaty of 1921, the Japanese had initially been limited as regards the size of their first aircraft carriers and because some of them were amazingly small, the strategy of massing several together as a task force fleet made sense. Pearl Harbour had illustrated the point convincingly and in the wake of that action, the Japanese carrier task force provided a powerful spearhead for many invasion plans. In February 1942, the Japanese aircraft carrier task force (Akagi, Hiryū, Sōryū and Kaga) launched aircraft to bomb Australian air bases and the port at Darwin. It was the first of sixty-two Japanese aerial attacks on the Australian continent that occurred between 1941 and 1943.

Japan then turned their attention to conquest in the Indian Ocean with the carrier task force once again spearheading the overall attack and where British Admiral Sir James Somerville, CIC Indian Ocean Fleet, took most of his ships to Addu Attoll in the Maldives. Crucially, the British aircraft carrier HMS Hermes was left in Trincomalee in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) for repairs.

On the 4th April 1942, the Japanese carrier fleet commanded by Admiral Chuichi Nagumo was spotted by a Catalina PBY and its position was transmitted back to its base in Ceylon. Despite this, the 'Easter Sunday' Japanese aerial raid on Colombo was a complete success and where radars had been switched off for maintenance over the weekend! It had also been a Sunday when Pearl Harbour had been attacked but Colombo was a much smaller incident! The British ships that Nagumo had expected to be there weren't and there were obvious signs that Japanese Intelligence was far less precise than it had been at Pearl Harbour with some planes attacking hospitals in the belief they were barracks and where other buildings were targetted on wrongful assumptions of that kind. In this battle, the British lost twenty-seven planes against the five lost by Japan.

In the late afternoon on 5 April 1942, two Royal Navy Albacores operating from aircraft carriers HMS Formidable and HMS Indomitable sighted the Japanese carrier task force but one was shot down and the other badly damaged before an accurate report could be completed. On the night of 5th April, Admiral Somerville used limited resources to find the Japanese carriers but failed. The hope had been to apply ASV radar equipped Albacores but the retaliatory strikes never took place.

In the late afternoon on 5 April 1942, two Royal Navy Albacores operating from aircraft carriers HMS Formidable and HMS Indomitable sighted the Japanese carrier task force but one was shot down and the other badly damaged before an accurate report could be completed. On the night of 5th April, Admiral Somerville used limited resources to find the Japanese carriers but failed. The hope had been to apply ASV radar equipped Albacores but the retaliatory strikes never took place.

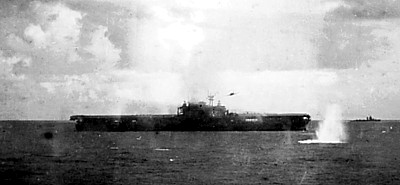

On the 9th April 1942, Japanese aircraft attacked the harbour at Trincomalee but were once again thwarted by the absence of the ships they had expected to find there. In truth, however, there had been a squadron there and including the British aircraft carrier HMS Hermes albeit without its aircraft of 814 squadron and undergoing repairs. All had fled to sea soon after the 'Easter Sunday' raid at Colombo had taken place. Nevertheless, a Japanese reconnaissance plane spotted Hermes off Batticaloa, and 70 Japanese bombers attacked the defenceless aircraft carrier forty times. The picture shows HMS Hermes sinking with the loss of 307 British sailors.

Other ships of the same squadron, heavy cruisers HMS Cornwall and Dorsetshire, and the Royal Australian Navy destroyer HMAS Vampire were also victim to this attack and sunk with heavy loss of life.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill described the events in this way during a visit to Washington; "The most dangerous moment of the War, and the one which caused me the greatest alarm, was when the Japanese Fleet was heading for Ceylon and the naval base there. The capture of Ceylon, the consequent control of the Indian Ocean, and the possibility at the same time of a German conquest of Egypt would have closed the ring and the future would have been black."

Fortunately, his fears were never realised on both fronts. In the Indian Ocean, Chuichi Nagumo's aircraft carrier task force had gone further than expected and where long supply chains were becoming more vulnerable to reprisal.

On April 18th, sixteen USAAF B25 'Mitchell' Bombers led by General Jimmy Doolittle were launched from the aircraft carrier USS Hornet (later sunk by enemy fire and the last major US fleet carrier to be lost during the war) and knowing they could never return because landing these large and heavy aircraft back on the short deck was impossible. The USAAF aircraft bombed several targets in Japan, mostly in Honshu albeit with modest damage, before proceeding towards the Chinese coastline and compelled to crash when the fuel ran out. Most crewmen were captured either by Chinese sympathisers or else by Japanese forces in occupation. Most were repatriated later but some were executed. It had been a mission to illustrate to ordinary people how Japanese cities were not safe from an American response and where their daily trust in the wisdom of their Japanese government might be tested.

In early May, 1942, Japanese tactical planners turned their attention to Port Moresby in New Guinea and Tulagi in the southeastern Solomon Islands. The US had however managed to decrypt enough of the radio signals messages being transmitted to the Japanese fleet to the extent of having some advanced knowledge of the Japanese intent. US Admiral Frank Fletcher commanded a fleet of two US carrier task forces plus a cruiser force of US and Australian ships and with orders to stop the Japanese invasions from succeeding. The Japanese fleet under the command of Shigeyoshi Inoue comprised two fleet aircraft carriers and one light carrier.

The Battle of the Coral Sea began on the 4th May 1942 and lasted for four days. The battle was the first ever action in which aircraft carriers engaged each other and in which neither ships sighted or fired directly upon the other. It began on the night of 3-4 May when Japanese troops successfully landed and occupied Tulagi and despite several Japanese ships being sunk or damaged by aircraft launched from the USS Yorktown. Now suddenly aware of the presence of US carriers in the area, the Japanese fleet carriers were charged with the intent of finding the US carriers and destroying them.

On May 7th and May 8th, carrier aircraft from both sides attacked each other. On that first day, US aircraft sank the light carrier Shōhō whilst losing a destroyer and an oil tanker. On the 8th May, both the USS Yorktown and USS Lexington were heavily damaged with the latter scuttled as a consequence. The Japanese fleet carrier IJN Shōkaku was heavily damaged while the IJN Zuikaku had lost most of its aircraft compliment and compelling Shigeyoshi Inoue to cancel the invasion of Port Moresby in the absence of air cover and in the hope they might come back in the near future to accomplish the invasion.

Both sides retreated from the area in order to execute repairs and refueling of their respective forces.

Although technically, a victory for the Imperial Japanese Navy, it would later prove to be a crucial moment in the war in which the seemingly unstoppable Japanese advances had in part been halted and where the two Japanese fleet carriers, Shōkaku and Zuikaku, could not actively contribute to the larger and more ambitious Battle of Midway operation already in planning.

It began as a theory in which US Intelligence was barely capable of cracking one word in ten of Japanese commuication codes but the increased frequency of such coded information was sufficent to indicate the Japanese were planning something of great significance and enormity. A vague reference from an aircraft communication almost a year beforehand indicated presence close to the Midway Islands and rightly named on account of their position in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. Indeed, the notion was even tested by placing false information inside regular US communication traffic with the isles and where codebreakers witnessed Japanese counterparts making reports about the non-existent situation and strongly indicating that Midway was the next intended target for the Japanese Navy. In terms of strategic value, Midway was located thirteen miles from Hawaii and permitted American air strikes on Wake Island plus an ideal refuelling stop for submarines and thus extending their range by a significant factor.

In the immediate days preceding the Battle of Midway, US Admiral Chester Nimitz made crucial decisions. Admiral Halsey was in hospital and recommended his own replacement. Raymond Spruance, a former cruiser captain serving with Admiral Halsey's American fleet became elevated to the role of Admiral in charge of the aircraft carriers USS Hornet and USS Enterprise with immediate orders to sail for Midway. The battle damaged aicraft carrier USS Yorktown, under command of Admiral Fletcher, returning to Pearl Harbour for repairs was granted a minimal seventy-two hour reprise before being ordered back into action with shipyard workmen still aboard conducting repair work from the previous battle. Additional aircraft and armaments were transferred to Midway.

There was naturally great concern in Japan about the Midway proposal and for a time, it seemed those who opposed it might win the argument but when Admiral Yamamoto offered his resignation if the attack was cancelled, most of the political opposition faded away. Operation MI became an important priority and where the primary objective was to draw American carriers and battleships into a major battle after Midway had been taken and where American capital ships were likely to be sent in response. By then, Japanese submarines would be in place to form a picket line akin to that planned by Admiral Scheer at the Battle of Jutland described above.

In terms of execution and expectation, the highly successful carrier task force led by Chuichi Nagumo and his stalwart Air Commander Genda would lead the attack in order to secure air superiority over Midway before a second group comprising the Japanese fleet of battleships and cruisers under the command of Admiral Kondo would actually conduct the invasion whilst providing major resources for a fleet to fleet battle against the expected American response. In this way, Yamamoto believed he could redress the absence of American carriers at Pearl Harbour in 1941 and where any attempt to repeat that attack was no longer a viable proposition. There is no doubt that he was aware that the USS Saratoga was being repaired in US shipyards on the west coast but it's less certain whether he knew the USS Yorktown, although extensively damaged, had survived Corel Sea and had been hastily withrawn to Pearl Harbour for repairs. It seems plausible that he may have believed the USS Yorktown had sunk some time after the battle.

In Japan, there was realisation just how bruising the Battle of the Corel Sea had been with the carriers IJN Shokaku and IJN Zuikaku deemed unfit for the major offensive on Midway. IJN Shokaku had taken three hits through her flight deck and needed months of repair work whilst IJN Zuikaku had lost many planes and pilots. Shokaku's air group was transferred to Zuikaku yet still leaving a shortfall since there were insufficient numbers of trained replacement pilots available. While IJN Shokaku remained in port, the IJN Zuikaku became the main ship of a naval force intended to attack the Aleutian Isles as a diversionary tactic and with that attack supposedly to take place just as the Battle of Midway was begun. Bad weather and delays actually meant that the Aleutian attack took place one day earlier than planned but US Admiral Chester Nimitz failed to take the bait and remained committed to the belief that Midway remained the primary target. By then, the three US aircraft carriers had assembled north-east of Midway at a position referred to as 'Point Luck'.

An important part of the plan involved a Kawanishi H8K Flying Boat to overfly Pearl Harbour in advance of this battle to spot whether the warships and aircraft carriers were still in harbour. In the event, however, refuelling submarines sent to the French Frigate Shoals discovered the normally deserted area occupied by American warships investigating a previous Japanese operation that took place in March and strongly suspected of having been the refuelling point during that operation. Consequently, 'Operation K' was cancelled and neither Yamamoto nor Nagumo were aware of this due to strict radio silence orders.

An important part of the plan involved a Kawanishi H8K Flying Boat to overfly Pearl Harbour in advance of this battle to spot whether the warships and aircraft carriers were still in harbour. In the event, however, refuelling submarines sent to the French Frigate Shoals discovered the normally deserted area occupied by American warships investigating a previous Japanese operation that took place in March and strongly suspected of having been the refuelling point during that operation. Consequently, 'Operation K' was cancelled and neither Yamamoto nor Nagumo were aware of this due to strict radio silence orders.

It was actually nine American B-17 Fortress aircraft on the 3rd June who became the first components of the engagement when they spotted the Japanese transport group and attempted to bomb it but without success. At 01:00 hours, a Catalina PBY successfully torpedoed the Japanese oil tanker 'Akebono Maru' and this became the one and only time during the battle where the US successfully undertook a torpedo attack on the enemy!

At 04:30 on 4 June, Nagumo launched his initial attack on Midway itself, comprising 36 Aichi D3A dive bombers and 36 Nakajima B5N torpedo bombers, escorted by 36 Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters. At the same time, the combat air patrol (CAP) to provide aerial defence for the fleet was put in place. Eight search aircraft were also launched to scout the immediate area but one, launched from the the heavy cruiser 'Tone' was launched 30 minutes late due to technical difficulties.

Shortly after six o'clock, American radars on Midway detected the Japanese aircraft and launched their aircraft but these proved no match for the Japanese squadrons who destroyed all of them within minutes. At 06:20, Japanese bombs were raining down on Midway!

According to the Japanese plan, that first attack should have been enough but it quickly became clear that Midway was still sufficiently operational as to present a threat. As standing practice within the Japanese Navy at that time, Nagumo had reserved fifty per cent of his aerial capacity in reserve. His CAG Fuchida urged a further attack and Nagumo agreed. The reserve aircraft began to be armed with bombs for the second strike but at 07:40, the scoutplane from the 'Tone' reported enemy vessels in relatively close proximity and where a more detailed report eventually established the presence of at least one American aircraft carrier located near Midway rather than Pearl Harbour!

Nagumo immediately reversed his previous orders and had planes rearmed with torpedoes and which eventually led to a stack of bombs being left on the decks of his ships in order to fulfil his order with haste. In addition, there was great concern about the timing since aircraft returning from Midway would require use of the landing decks at a time when they might have been able to launch counterstrike aircraft. In addition, CAP aircraft charged with defending the fleet were low on fuel and also demanding use of the flight decks. Nagumo chose to recover the CAP and other aircraft returning from the strike on Midway before launching his counter attack.

By contrast, the US fleet had now correctly guessed the intent and had long passed the 'picket submarine' intended to present challenge to them and in a similar way akin to the Battle of Jutland described above. Even as the first news concerning the first strike on Miday confirmed their suspicions, the USS Enterprise and USS Hornet changed course into the wind and launched their first aircraft shortly after 06:00 and in the knowledge of the extreme range.

It's at this point when a few minutes of careful thought might have rendered greater success with reduced losses and where the uncoordinated attacks by successive American air groups at different times typically resulted in disaster. Bomber and torpedo squadrons were quickly annhiliated without presence of fighter escorts. The Japanese carriers survived many of the initial American aerial attacks without major damage.

By chance, three squadrons of American SBDs from Enterprise and Yorktown, respectively approached from the northeast and southwest. They were running low on fuel because of the time spent looking for the enemy. However, squadron Commander C. Wade McClusky, Jr. decided to continue the search and by good fortune spotted the wake of the Japanese destroyer 'Arashi' running at flank speed to rejoin Nagumo's carriers after having unsuccessfully depth-charged the US submarine Nautilus and which had earlier unsuccessfully attacked the battleship Kirishima.

McClusky's decision to continue the search, "decided the fate of our carrier task force and our forces at Midway." in the words of Admiral Chester Nimitz writing later and afterward. It was the crucial moment when the Japanese CAP had just repulsed another attack and where they were widely dispersed in pursuit activities and leaving the fleet vulnerable to air attack.

Beginning at 10:22, the assorted aircrew from different US ships scored hits on the IJN Kaga with the IJN Akagi being attacked four minutes later by three bombers. Yorktown's VB-3 squadron, commanded by Max Leslie, went for Sōryū, and scored major hits. The dive-bombers left Sōryū and Kaga ablaze within six minutes. Akagi was hit by just one bomb (dropped by Lieutenant Commander Best), which penetrated into the upper hangar deck and exploded among the armed and fueled aircraft there. One bomb exploded underwater very close astern; the resulting geyser bent the flight deck upward and also caused crucial rudder damage. Sōryū took three bombs in her hangar deck, Kaga at least four, and possibly five. All three carriers were out of action and were eventually abandoned, scuttled and sunk.

In major part, the extent of the damage was caused by orders concerning the re-arming of the aircraft and where bombs crowded the flight deck during the attack. Only the Japanese aircraft carrier Hiryū proved fortunate within her sandwiched position between Sōryū, Kaga and Akagi. She received no hits and remained fully operational. While Nagumo transferred his flag to a lesser ship, Vice Admiral Tamom Yamaguchi aboard Hiryū ordered a counterstrike in the false belief that only one American aircraft carrier was still in close proximity.

In reality, two separate attacks had been directed against the USS Yorktown and where each had been severe. The first had stopped her engines but where she had been restored to service within an hour. Upon the second attack, the 'old lady' had given all she could and sank while many aircraft were quickly transferred to the USS Enterprise and USS Hornet. The reprisal attack on Hiryū from the USS Enterprise ended with the Hiryū being sunk.

Following far behind the carrier task force, CIC Admiral Yamamoto was given the news much later and where he felt bound to cancel the invasion of Midway and personally apologise to his Imperial Majesty for the failure and disaster. The crucial absence of the American aircraft carriers at Pearl Harbour had proved to be his undoing.

More importantly from a European perspective, the Americans were enabled to dispatch more troops into the European theatre since a Japanese attack on the US mainland became less likely. Midway proved to the furthest extent of Japanese influence and where US Admirals steadily revised their methods of attack and invasion.

By June 1942, Allied forces in the Pacific began to take the offensive. Operation 'Watchtower' began on August 7th 1942 when Allied forces landed troops on the islands of Guadalcanal, Tulagi and Florida with the former British protectorates of the Solomon Island group. The objective was to deny Japanese use of airstrips being built there and which could threaten seaborne communications between the US, Australia and New Zealand. The invasion took the Japanese forces by surprise and where the airfeild under construction on Guadalcanal was renamed 'Henderson Field' following the success of the invasion.

The Japanese response was predictably rapid with bombing raids taking place almost every day while Japanese warships sought to reinforce their army strength on Guadalcanal but were forced to undertake such work during the night as aircraft from Henderson Field often spotted the supply ships during daylight hours. On many of the other Soloman Isles attacked by the Allies, the defenders had almost literally fought to the last man and providing a foretaste of the bitter land struggles ahead.